The Invisible Blinds: Unveiling Cognitive Blind Spots in Our Everyday Judgments

The Dunning-Kruger effect explains a paradox: the less competent people are in a certain area, the less capable they are of recognizing their own incompetence.

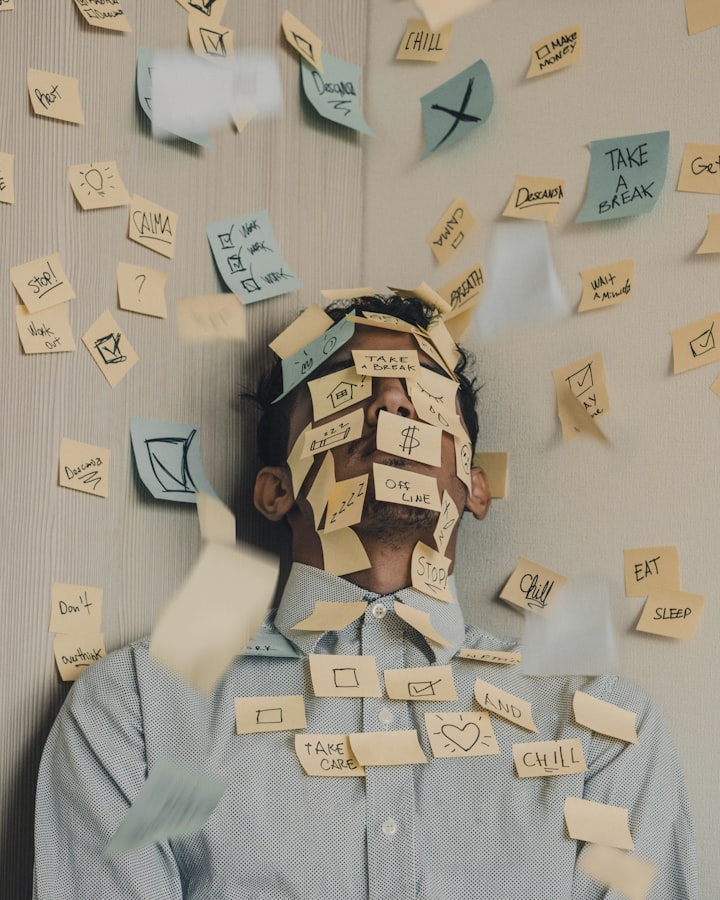

Have you ever encountered someone at work who, despite their best efforts, seems perpetually off the mark? Picture a colleague – let's call him Buddy – whose reports are always riddled with errors, yet he remains blissfully unaware of his shortcomings. It's not that Buddy chooses to ignore his mistakes; rather, he genuinely doesn't realize they exist. This phenomenon isn't just an odd quirk of Buddy's; it's a scientifically recognized cognitive bias known as the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Named after the researchers who first identified it, the Dunning-Kruger effect explains a paradox: the less competent people are in a certain area, the less capable they are of recognizing their own incompetence. This concept isn't merely an abstract theory; it was vividly illustrated in a 2009 study, "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead To Inflated Self-Assessments". The study revealed that not only do individuals lacking in specific skills often arrive at incorrect conclusions and make poor choices, but their lack of expertise also blinds them to their own limitations.

This disconnect manifests in various ways. Students with mediocre academic performance have a harder time accurately assessing their abilities compared to their more competent peers. Similarly, less skilled readers struggle to evaluate their understanding of a text as effectively as proficient readers do. So, when Buddy mistakenly believes that Romeo and Juliet succumbed to the Swine Flu, it's not a simple case of him being a poor reader; rather, he lacks the very framework of skills that define good reading comprehension.

The research by Kruger and Dunning, dating back to the late 1990s and culminating in their 2009 paper, involved asking participants a series of questions and then having them rate their own performance. The results were telling: those who fared poorly (in the 10th to 15th percentile) grossly overestimated their abilities, often placing themselves around the 65th percentile. Conversely, those with higher scores tended to underestimate their own expertise.

These findings take on a deeper meaning when we consider the case of a bank robber, cited by Kruger and Dunning, who covered his face in lemon juice thinking it would render him invisible. His baffled reaction upon being caught wasn’t that his plan was flawed, but disbelief that the lemon juice hadn't worked. This extreme example highlights not only the Dunning-Kruger effect but also draws a parallel to anosognosia – a condition where individuals are unaware of their own disabilities, such as patients with left-side paralysis inventing reasons for their inability to move, rather than acknowledging their paralysis.

In reflecting on these insights, we're led to a crucial realization: the importance of self-awareness and honest feedback. In a culture where grade inflation and permissive standards often mask underperformance, we risk reinforcing misconceptions like Buddy's. By skirting around the truth, we may inadvertently leave individuals ensconced in their false sense of competence.

The journey towards true understanding and self-improvement begins with a clear mirror. It's not just about correcting errors; it's about nurturing an environment where we can recognize and embrace our limitations, and thus, grow. For in the end, it's not swine flu that obscures the tragic beauty of Romeo and Juliet's tale, but our own unacknowledged cognitive veils.